By KEVIN YANEY

History Right Here

The roots of the American Civil War grew deep in the soil of Hamilton County 200 years ago. Indiana was a free state – one that did not allow slavery to exist within its borders. However, that did not mean that everyone in the state was an abolitionist – far from it.

It has been 160 years since slavery was outlawed by the Thirteenth Amendment. How did the residents of Hamilton County play a role in the slavery debate? Let’s take a look back at our history.

On July 13, 1787, a very significant paper was signed by the leaders of the fledgling government of the United States. The Northwest Ordinance was a document that defined how the territory that eventually made up all or part of six states was to be governed, how the land would be divided, and defined the rights of the people living there. Indiana was one of those states. In particular, the Northwest Ordinance banned slavery in the territory, but did not prohibit fugitives from slavery from being captured and returned to their owners in other states.

Those two items would come into conflict right here in Hamilton County, Ind., in the decades that followed.

As land deeds were parceled out to pioneers who settled in the Territory, a group of Christians from the Society of Friends, or Quakers, began to show up in the early part of the 19th century.

Quakers believed in hard work and living simple lives. Many of them were farmers. They were non-violent and they believed strongly in helping the downtrodden. They had come to a belief that no one should be enslaved by another. Those Quakers who were living in states where slavery was legal – particularly Virginia and North Carolina – were attracted to the Northwest Territory because of its prohibition of slavery. So were other Christians who had anti-slavery leanings.

However, some of these Christians had taken their anti-slavery beliefs to another level. One of those was George Boxley who, in 1816, was living in Virginia and was arrested and accused of leading a slave rebellion. He was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. As the story goes, his wife sewed a saw blade in the hem of her dress and went to see her husband in jail. The night before he was to be executed, George Boxley cut his way out of his jail cell and escaped. After several years on the lam, George and his family settled in Hamilton County in 1828. The Boxley cabin was built over a rather large cellar.

Four years later, Asa Bales and his wife, Susannah, arrived in Hamilton County. They attracted more Quakers to the area and called their settlement Westfield. Soon, the town of Westfield began to attract more and more Quakers.

That was not all the area attracted.

Fugitive slaves were known to travel through the area. Several Quakers were known to give aid and shelter to them. Asa Bales became an outspoken abolitionist. He took to the lecturing circuit, became politically active, wrote in abolitionist publications, and in 1840, became the president of the Hamilton County Anti-slavery Society.

But there was a problem growing in the church. Could you be a good Quaker if you were breaking the law? Remember, the Northwest Ordinance made slavery illegal, but it also stated that if runaway slaves were apprehended in the territory, they would be returned to their owners. The Westfield Friends split over this issue. More than 100 families were disowned by the Westfield Monthly Fellowship for their actions in helping fugitive slaves. These families formed the Westfield Anti-slavery Society of Friends Yearly Fellowship. Their meeting house and cemetery are on the property owned by Asa and Susannah Bales.

The Quakers were not the only abolitionists in Indiana. Nationally, the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians all had church splits over the slavery issue. In Hamilton County, the Anti-slavery Friends began to cooperate with Wesleyan Methodists, in particular, to move freedom-seeking fugitives in and out of the area. There was a rather large swamp north of Westfield known as the Dismal Swamp, where fugitives were often hidden.

As time went on, the laws concerning runaway slaves became more stringent. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act made it a federal crime to resist the capture and return of escaped slaves to their owners. In response, Indiana passed a law denying access to the state if you were of African descent – whether you were free or enslaved. Abolitionists were outraged and their actions became more radicalized.

When violence broke out in Kansas over the slavery issue, many abolitionists took more militant actions. This led to the killing of both anti-slavery and pro-slavery proponents in Kansas.

What were non-violent Quakers to do? When war broke out and there was a call for volunteers in Indiana to take up arms against the South, there were several members of the Westfield Anti-slavery Fellowship who volunteered for service in the war.

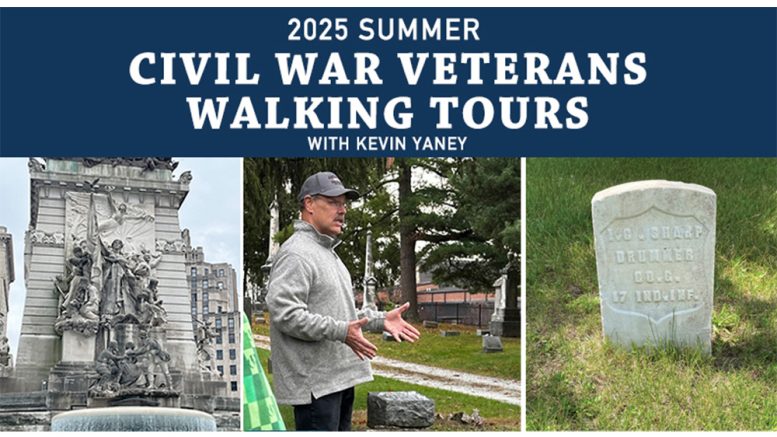

There are 11 Civil War veterans buried in the Anti-slavery Friends Cemetery at Asa Bales Park in Westfield. On June 21 at 10 a.m., I will be leading a walking tour of the cemetery and will be talking about these men who served in these most difficult days.

If you want to hear more about the people who were a part of aiding fugitive slaves in gaining their freedom, you are invited to the event. The tour is free, but you need to register. You can do so at CivilWarVeteransWalkingTour.com.

Be the first to comment on "Westfield’s Anti-slavery Friends Cemetery Tour"