By SCOTT SAALMAN

Scarmouch

Before Mom’s cancer, Dad and I bonded in the evening during kitchen table Scrabble wars. From the living room, Mom, unseen, cackled at Two And A Half Men’s rapid fire double entendres, causing me to close the kitchen door to focus better. Dad and I were happily lost in competition while Mom was happily lost in her favorite comedy.

Before Mom’s cancer, Dad and I bonded in the evening during kitchen table Scrabble wars. From the living room, Mom, unseen, cackled at Two And A Half Men’s rapid fire double entendres, causing me to close the kitchen door to focus better. Dad and I were happily lost in competition while Mom was happily lost in her favorite comedy.

All was good with the world.

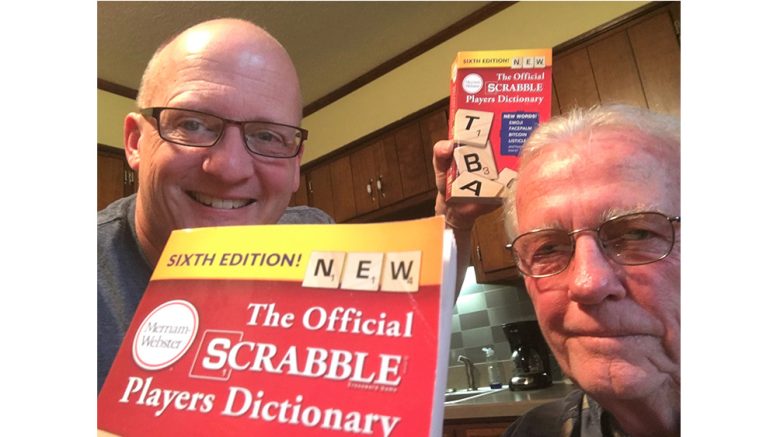

Scrabble was my connection with Dad. The board was one of those deluxe rotating beauties. It bloomed between us with each letter we planted to fill in the grid’s 225 spaces.

We seldom spoke. We were too lost in our word-forming strategies, sometimes on the offense, sometimes on the defense. We communicated through spelling, not speaking. Neither wanted to merely win, we wanted to annihilate. Egos at stake.

Photo provided

Sometimes our fingertips touched our respective board sides simultaneously, as if stationed at a Ouija board, a father and son Scrabble séance conjuring literate spirits to spell out words otherwise unspoken between us, building a bridge for two men taking comfort in dual states of incommunicado.

We did, though, voice our word scores throughout. As the automatic scorekeeper, I kept a tally.

All this while Mom laughed aloud, alone, in the living room.

Sometimes, Dad tried to distract me by offering food when it was my turn to play.

“Would you like an apple?”

“No.”

“It’s a good apple.”

“No.”

“Would you like a peach?”

“I’m concentrating, Dad.”

“It’s a good peach.”

“Dad.”

“I’ll slice you a tomato.”

It was as if the kitchen had transformed into a roadside fruit stand.

I accepted a banana once. The game was going long, and I was hungry. As I unpeeled, he warned, “Careful. Bananas will stop you up.” All my life, Dad exuded wisdom about all things A to Z that “stop you up.” He should publish an encyclopedia.

“If bananas stop you up, Dad, then where exactly are you inserting the banana?”

I took big bites from the banana, chewed vigorously, chimp-chomped, made a big show of it, just to demonstrate my defiance to his advice. Secretly, the fear of possible rectal restriction definitely hindered my focus, as if my voodoo dad had placed a curse on me. Mind games. The man was shameless.

We stopped playing Scrabble soon after Mom was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer. I spent more time watching Two And A Half Men with her.

“Why don’t you play Scrabble tonight?” she asked during a commercial. “Your dad misses it.”

“I’m tired of Scrabble,” I lied. “Besides, Dad cheats. He distracts me with fruit and constipation.” Mom laughed. I wanted to tell her that I’d rather be with her in the living room than with him in the kitchen, which was true, but that bordered on acknowledging her disease. Believing it was my duty to get her mind off her cancer, I seldom spoke about it. I worried my worry would make her worry. I should’ve spent more time talking to her before she became sick, so it didn’t seem so obvious why I was spending more time with her now. Historically, Scrabble, in the guise of quality time with Dad, had distracted me from quality time with Mom.

Last fall, Mom lost her five-year cancer battle. She died during hospice in the living room. All rooms, I guess, are living rooms, until they’re not.

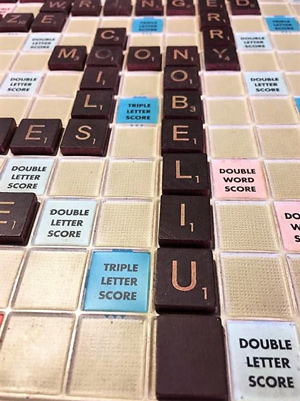

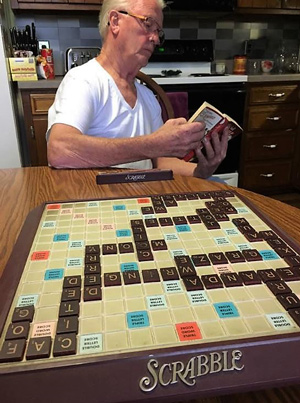

A half-year passed before we played Scrabble again. I sat in my usual seat at the kitchen table with my back to the west window while Dad sat across from me. As he shifted the letters around on his rack, I sneakily adjusted the blinds behind me so that the setting sun’s brightness assaulted his vision and played havoc with his concentration.

The silence between us seemed heavier.

Photo provided

“Close the blinds,” Dad said.

Dad’s first word used all seven tiles. In Scrabble lingo, that’s a bingo. “Fifty-eight,” he said. I double-checked his math. Jotted 58.

I studied the Scrabble tiles on my rack. No Two And A Half Men sounded from the living room. No mother’s laughter tried to distract me. No need to close the kitchen door.

I had a blank on my rack, which is always promising. I played a seven-letter word. “Sixty-eight,” I said, already 10 points ahead.

The house never seemed so quiet.

A THUMP coming from the living room startled me. Then, another THUMP.

Dad kept his head down, juxtaposing his second-round tiles on his rack, as if he hadn’t heard.

“What’s that noise?” I asked.

Dad smiled. He had heard. “It’s your mom.”

THUMP.

“What?”

THUMP.

Again, the Ouija board.

“It’s a cardinal,” he said. “It keeps crashing into the window.”

THUMP.

“It’s done that for days,” Dad said. “Usually in the evening.”

He seemed unfazed by the kamikaze cardinal. I worried the state bird might kill itself.

THUMP.

“Can’t you scare it off?”

“Your mom always said she would come back as a cardinal.”

I glanced up from my letters, making rare eye contact. I saw it spelled out in his blue eyes: B-E-L-I-E-F.

THUMP.

“Shut the kitchen door if it bothers you,” he said.

THUMP.

Each thump a lump in my throat.

Mom wanted back in.

“Thirty,” he said, ahead 20 points.

I missed her laughter. I closed the door. We had a game to play. We were living.

Contact: scottsaalman@gmail.com. Buy Scott’s books on Amazon.