By SCOTT SAALMAN

Scaramouch

I’ve been thinking about tennis.

I’ve been thinking about tennis.

I miss the “ker pock … ker pock … ker pock” during the long rallies of my youth, the ball bouncing off the asphalt (“ker”) followed by the quick collision with catgut (“pock”), the squeaks of sneakers and the wonderful poof at the opening of a new can of balls, each connection of tight strings on fresh balls filling the air with bursts of yellow fuzz.

I have been thinking about tennis because I just watched the recent, great Showtime documentary, McEnroe. In high school, I wanted to be John McEnroe.

But before then, in 1976, I was given my first tennis racket on my 12th birthday. Mom wrapped the racket so as not to ruin the surprise. My parents must’ve thought I was really stupid, not being able to identify a wrapped tennis racket. I bet tuba-playing kids go through the same thing. “Is it a Big Wheel?” I asked, holding up the wrapped package, just to make Mom and Dad feel good.

I was excited about the tennis racket but was overcome with disappointment when I discovered it wasn’t the metal-framed Jimmy Connors-endorsed T-2000 I wanted. Instead, it was a used, wooden-framed racket with the name Ann Jones written on it. A girl’s racket! I feigned appreciation, taking a few half-hearted strokes in the living room, fearing any second I would begin developing breasts. “At least it’s not a tuba,” I likely mumbled. Luckily, it was late November, too cold for outdoor tennis. By summer, I forgot I even had a racket. That’s one benefit of winter birthdays.

A few years later, though, something life-changing happened. I watched the dramatic 1980 Wimbledon Championship between Bjorn Borg and McEnroe on NBC. Suddenly, I wanted to be McEnroe. I loved his bad-boy antics. I begged my parents for a new tennis racquet. I assured them I would pay them back once I won Wimbledon. They fell for it. They had no idea what Wimbledon even was. With my new racket, a male one this time, tennis became an obsession.

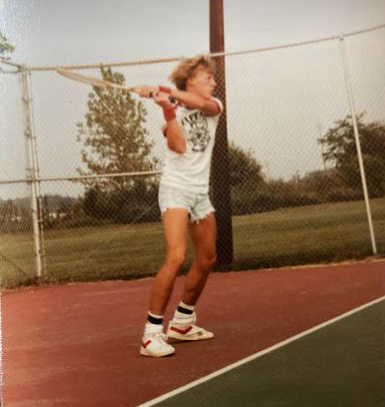

Scott Saalman playing tennis in 1983. (Photo provided)

Two or three matches during a single summer day were not unusual. Hand and foot blisters were common. The 90- to 100-degree days of July and August didn’t matter. To stay hydrated, I filled the tennis ball can – they were metal then – with warm water from the nearby fountain, each sip tasting like rust and tennis ball chemicals. It likely stunted my growth. Made my hair fall out. Between matches, I’d get a chili dog at Dairy Queen and resume play without gastrointestinal repercussions. My skin went from lobster red to bronze in just a few days.

I was a scrappy, top-spinning, loudmouthed, human backboard type of player. I had no backhand. My second serve was so slow it actually went in reverse. My canvas tennis shoes would rip after only a couple of matches, and I would wrap them with Dad’s electrician’s tape.

With no prior lessons, I joined the Tell City High School Marksmen tennis team. Our coach, also new to the sport, sat in his car and sipped a beer while we ran laps. He reminded me of the coach (Walter Matthau) on The Bad News Bears. We were The Bad News Marksmen.

I played number three singles my first year.

Inspired by McEnroe’s showmanship, I made a spectacle of myself, grunting and jumping with each stroke, diving for the out-of-reach shots as if the asphalt were Wimbledon grass (a little blood never hurt anyone), rolling, sliding like a clay court specialist (this technique caused me to tear my ACL during a match in my 30s), climbing fences, yelling at myself for my boneheaded blunders, and cussing out the tennis ball for its mutinous spirit when losing a point. I would hold the ball up to my face and exclaim, “There’s one in every can!” My teammates ate it up. They nicknamed me “Gazelle” because of my exaggerated, ballet-like leaps during returns.

Though I was a local bad boy of tennis, Mom never missed a match. She applauded with zeal when opponents double faulted, making her, I guess, “the bad mom of tennis.” An Evansville kid, after hearing her squeal with unsportsmanlike delight when he served a ball into the net, asked during changeover, “Who is that #$%&?” To which I replied, “That #$%& is my mom.” I hacked him to death in the third set – in Mom’s honor.

Our team never won a title, often thwarted by the dreaded Jasper Wildcats, historically one of the best tennis programs south of Indy. Anytime Jasper was next on our schedule, we’d plead with our coach, “Do we really have to show up?” He’d burp.

I experienced only one memorable match against Jasper. I scrapped my way into a third set. “Hit it to his backhand. Hit it to his backhand,” my opponent’s teammates shouted then. Even their parents shouted, “Hit it to his backhand.” It was such an infectious chant that I swore I heard my own teammates shout it. Yes, every shot my opponent made went to my backhand. I looked at Coach for advice. I read his lips: “I need a beer.” The third set ended quickly. I lost.

In tennis, I was better than some but worse than most. I never made it to Wimbledon. Sorry, Mom and Dad. Still, God love you, Johnny Mac.

Contact: scottsaalman@gmail.com. Buy Scott’s books on Amazon.