In 2019, I toured the mammoth Toyota Motor Manufacturing Indiana (TMMI) plant in Princeton, Ind.

How big is TMMI?

The tour involves boarding a tram.

Need I say more?

At 4.3 million square feet, TMMI is a manufacturing marvel that mixes high-tech robotics with a high-skilled workforce to create Highlander, Sequoia, and Sienna.

A vehicle is created from start to finish in about 20 hours. Thousands of vehicles A DAY are made there.

I saw robots and controlled sparks and autonomous carriers (the future is now). I saw teams of employees – thousands work there – who smiled and waved as our two tour trams approached.

About 15 minutes in, the most unexpected of magical things happened.

I noticed several green plastic boxes with clear lids displayed at various workstations.

It took a moment for their purpose to come into my mind’s focus.

Lockout-tagout boxes.

I lost my breath.

Lockout-tagout is a safety procedure used in industry to ensure that dangerous machines are properly shut off and not able to be started up again prior to the completion of maintenance or repair work. The boxes support the procedure.

They save lives.

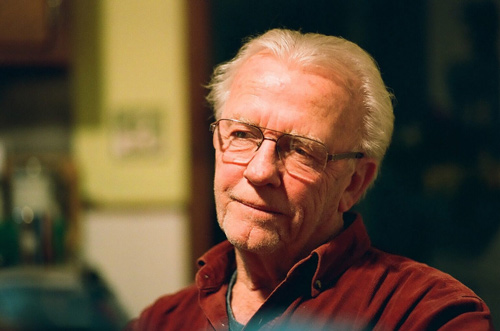

Scott’s father, Marion Saalman, thought of the idea of the Lockout/Tagout Box and was able to bring his idea to fruition in 1992 and operate it as a side business while keeping his job as a union worker at an aluminum plant. (Photos provided)

Their sighting came as a happy surprise, leaving me with one thought: Dad.

The green boxes were a customized version of the Saalman Safety System Group Lockout/Tagout Box that my dad patented as a sideline business in 1992.

I remain in awe of him for having the wherewithal to bring his idea to fruition. Even though at that time he was earning union wage at an aluminum plant, it would have been very easy to stick with the status quo and avoid a financial risk that might or might not earn him enough money to be his own boss one day.

My parents never took money lightly. When they married, they were poor. A shotgun wedding in 1962 (both wedding bands totaled $40). A big move from Tell City to Jasper to find work. The baby (Kimberly Lee) born too prematurely for survival. Birthed and buried in one day, she lies eternally in Dubois County dirt in the shadow of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

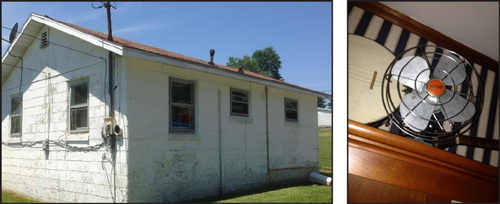

Briefly, they rented in a neighborhood nicknamed Frog Town, a derogatory designation for a not-so-idyllic location. They had to make promissory payments for a seven-dollar, eight-inch, electric fan.

They never threw away the fan, keeping it displayed like a well-preserved museum piece in their Tell City ranch house built in 1967. It was a reminder of the tough times my parents faced.

(Above left) When Scott was born in 1964, he and his family lived in this small cinder block home in Tell City. (Above right) His parents never threw away this eight-inch desk fan, instead keeping it as a reminder of tough times. (Photos provided)

When I was born in 1964, we lived in a cinder-block house adjacent to a back alley in Tell City, the home the size of a two-car garage – if that.

Dad convinced Mom that he was onto a good idea. As a lifelong machinist and maintenance employee who serviced large machinery, he knew how important his box would be to the safety of U.S. workers.

In 1998, at 53, as a major strike loomed, he accepted a generous severance package that promised lifetime healthcare benefits, a feature that proved very valuable when Mom was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer in 2016.

His box was featured in major safety catalogs. The safety companies faxed and emailed purchase orders to him. When the orders became too much to handle, Mom traded in her restaurant hostess job to become Dad’s office manager. She forwarded the POs to a plastics plant that produced the boxes. The boxes were shipped to steel, aluminum, borax, and boron mills; to power plants, chemical plants and oil refineries; to major beer breweries, huge Canadian sawmills, and automotive plants. Mom stuck thumb tacks on a wall map where the boxes ended up, some tacks even flagging overseas locations.

Saalman Safety System was a mom-and-pop shop serving business behemoths. Its business model was so simplistic I doubt the term business model was ever even spoken between my parents. Their only overhead: a computer, a fax machine, a printer, a desk, all placed in my childhood bedroom. It was a consistent cash cow that I wish I could’ve milked.

Photo provided

I kidded myself that I would take over the family business one day. Ultimately, I lacked the courage (and money). When Mom’s cancer zapped her energy, they sold the business to an interested outsider. Dad was too involved in his own machine shop (Saalman Machine and Tool being another dream achieved) to effectively keep up with the box orders. My parents deservedly used the money to further enjoy their lives together.

I had a general idea of Saalman Safety System’s success, though I must confess that the boxes really meant nothing more to me than a growing number of multi-colored thumbtacks on a world map in my childhood bedroom. But not until the TMMI tour was I able to see Dad’s boxes actually being used within a major manufacturing arena. Suddenly, Dad’s box became real. Finally, the magnitude of my dad’s dream, his contribution to worker safety, and my parents’ courage and business savvy hit home.

At TMMI I came to terms with the fact that I am a son who’ll never be as successful as his old man. Dad set the bar too high, as heroes often do. From my arms, though, there sprouted goosebumps of a very proud son.

Contact: scottsaalman@gmail.com