White River Township’s Flanders family now in eighth generation of farming

Submitted by Hamilton County Bicentennial Commission

When James Monroe Flanders moved his herds of cattle and horses west from Ohio to what is now White River Township in the mid-1800s, he put down the roots of what has become one of the county’s most historically important farming families – now in its eighth generation.

While many Flanders have worked the land, in honor of Women’s History Month, this story recognizes the life and legacy of Marie Flanders, one of the family’s most influential figures.

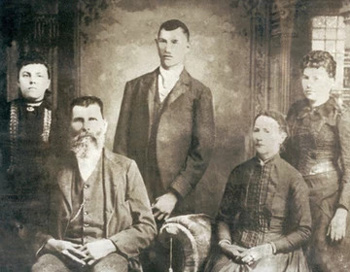

(Seated) James Monroe Flanders and Sarah Flanders (Langdon’s wife). (Standing) J.M.’s son Langdon with his two sisters (unnamed). (Photo provided)

But before Marie came into the picture, her future great-great-father-in-law was setting the family business in motion. J.M. Flanders bought at least three parcels of land southeast of Strawtown during his lifetime. In 1854, he purchased 100 acres with a partner, Hamblin Shepard, who supplied horses to circuses that wintered in the area at that time.

When plans to build a rail terminal in Strawtown were canceled eight years later, J.M. bought the earmarked 160 acres from the railroad company. He also owned a 72-acre tract in the horseshoe prairie that is now part of Strawtown Koteewi Park. During the Civil War, the Union Army bought horses and beef cattle from Flanders.

Inexperienced in the ways of planting and harvesting, but in love with a man who was a farmer, Marie Spannuth married Ray Flanders in 1919. She became what her daughter-in-law Jeanne Flanders calls a “FarmHer,” a term coined by a project created in 2013 to celebrate women in agriculture.

Marie’s influence on the Flanders Farm

On the farm, Marie cared for hundreds of hens and processed eggs for sale to grocers in Noblesville and Anderson. Every Tuesday and Friday morning, she and her three sons candled each new egg to look for imperfections and placed the ones that passed inspection into cartons, bundling 30 cartons to an egg case.

They filled the trunk of Ray’s Pontiac with cases and stacked whatever was left in the backseat. Avoiding potholes and sharp turns as best he could, Ray drove the eggs to the grocery store that was buying them that day. He would return with payment for the eggs and whatever groceries Marie had on her list. Marie never got her driver’s license. Her busy days centered on the two-acre homestead.

In the early 1900s, many Indiana farms had a few milk cows for their own use and to produce milk to sell to a local dairy. Marie also kept a large garden to feed her family through the winter, canning much of what it produced and giving away part of it to neighbors. Even in the coldest weather, while working outside she wore a dress and black socks over her hose – never pants.

Marie and husband Ray Flanders (far right), with their sons Robert, Jim and Harold in 1942. (Photo provided)

Marie was also a meticulous bookkeeper. She kept four spiral notebooks, one for each son and one for Ray and her, recording all the farm’s finances, operations and big decisions.

Each morning, the men of the family gathered around her table to plan the day’s work. On most days she prepared mid-day dinner for everyone working on the farm, catering to each person’s favorite dishes. She stocked her refrigerator with quarts of chocolate milk for the men to take with them back to the field work.

She had her own way of getting things done, often in subtle ways. She told Jeanne that during the 1940s, after she and Ray had installed an LP (liquid propane) furnace in their home, she wanted the woodshed behind the house torn down. She considered it an eye sore. Ray didn’t see a need to tear it down, so each time she walked by that shed on her path to the chicken house, she would yank a loose board off the shed and put it in the burn barrel. Finally, in 1976, her sons took the shed down entirely. She felt she had finished her tasks.

Tending to a wider flock

When we reflect on our county’s history, we can report on more than facts and feats. We can also celebrate people’s less-tangible gifts.

Marie was generous. Young visitors enjoyed ice cream from the big freezer, and chocolate-covered peanuts and milk chocolate stars from the countertop. During summers, the grandkids rode bikes to grandma’s house for noon dinner.

She cared for relatives when they needed caring for after hospital stays, and Marie always had an extra plate of food ready for surprise guests at mealtimes. After a visit, she would offer friends and neighbors eggs to take home with them. People came back years later to thank Marie for her friendship and care.

Jeanne recalls the day Marie died.

“My family had our family’s yearly dental appointments. Our youngest son, Jerry, was not yet seeing the dentist and stayed with Grandma that morning. We returned after dinner from the appointments. She and Jerry were sitting at the kitchen table, and she was patting Jerry’s hand. As we left with Jerry, she walked to the car in her stocking feet to say goodbye one more time.

“During the next two hours, she washed the dishes from dinner. Usually she left the dishes in a drainer to use for the next meal. On this day she not only washed everything but dried and put every dish and pan in its place in cabinets. Everything seemed to be in its place in the house. She had gathered her eggs. Every egg was washed and ready to take to the grocery store. Marie had finished her task, she had run her race!”

After Marie and Ray passed away, their three sons divided the ownership of the property equally among them and continued farming together.

Flanders Farms in 2022

Today, the farm that J.M. Flanders founded has expanded and is divided among four Flanders families, each managing their own acreage plus ground they lease from other landowners.

Under the business name Flanders A-Maizing Grain, Jeanne and Jim Flanders’ primary crop is a waxy, food-grade specialty corn used as thickener for things like puddings or to make products such as toilet paper softer and more absorbent.

If you’re driving past a Flanders-farmed field, you might also see Plenish soybeans, used in healthy cooking oils.

About 40 people in the sixth, seventh and eighth generations of the Flanders family are currently farming land in White River Township. Some of them might have the same nose or hairline as a distant relative. But they also carry with them the impact of their ancestors’ stories – Marie Flanders’ chief among them.

Descendants of Ray and Marie Flanders at the Walnut Grove Community Center over Thanksgiving 2017. (Photo provided)